“It’s very tough to be a futurist. You need to have some clue that something is important out there. If I even see them talking about it, that might be enough for me to go and try and think about it myself first before I dive into the early thought leadership that’s coming out. And that’s what I believe made me more effective.”

– Dion Hinchcliffe

About Dion Hinchcliffe

Dion Hinchcliffe is an internationally recognized business strategist, enterprise architect, transformation consultant, futurist, analyst, and in-demand keynote speaker. He is currently VP and Principal Analyst at Constellation Research where he heads up research and global client advisory into CIO issues, the future of work, and emerging technology in the enterprise. Dion is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures on digital transformation and enterprise technology.

Blog: Dion Hinchcliffe

LinkedIn: Dion Hinchcliffe

Twitter: Dion Hinchcliffe

Facebook: Dion Hinchcliffe

What you will learn

- How to make sense of signals and trends (01:51)

- How to think in the noun-verb framework (04:58)

- What is the drawing diagram approach (06:19)

- How to avoid bias in making sense of new signals (09:25)

- Why we should be conscious to provide value to our peers (12:09)

- How to organise your ideas (16:04)

- What is between finding the underlying content and putting that into the structure? (18:00)

- What are the exciting developments in generative AI (21:19)

- What can you do to enhance your information, insight, and communication methodologies (24:45)

- How to make any concept or framework more compact (27:41)

Episode resources

Episode images

Transcript

Dion Hinchcliffe: Oh, it’s great to be here. Thanks for having me.

Ross: You make sense of enterprise technology, the future of work, changing organizations, and a lot more. How do you do that? How do you see all of the signals and the trends and make sense of them to get to work out where things are going?

Dion: What helps is my background is in enterprise architecture, and business architecture. You learn over years and decades about how to capture ideas in the abstract, and how to separate the uncounted details that don’t matter to what’s the core of the concept. As an enterprise architect, you have to take the ideas you have and communicate them, or they’ll not affect them. You don’t get people to uptake what you’re doing, or adopt your ideas or your way of thinking or your frameworks unless you have a convincing way of doing that. One of the big advantages I had that I came up in the 90s, where we had a lot of very rigorous discipline around organizing our ideas, framing them up, creating designs around them, architectures around them, frameworks around them, so that really helped.

Ross: In a way, you’ve become an architect of ideas.

Dion: You do. What’s interesting is enterprise architecture sounds like a very remote, abstract, unapproachable concept but it really is business architecture, how do we think about our businesses? How do we communicate what they do and how they work to everyone? It is a vitally important discipline.

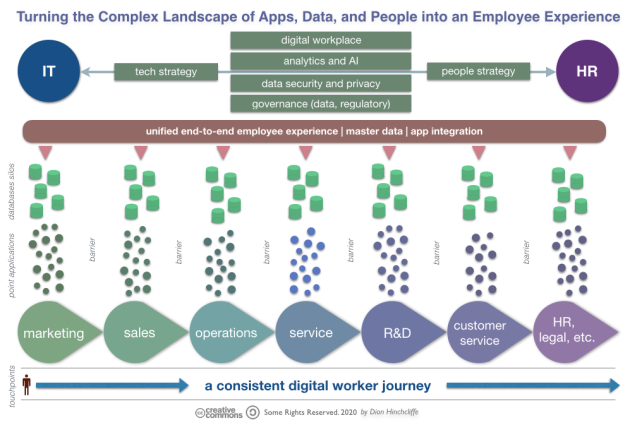

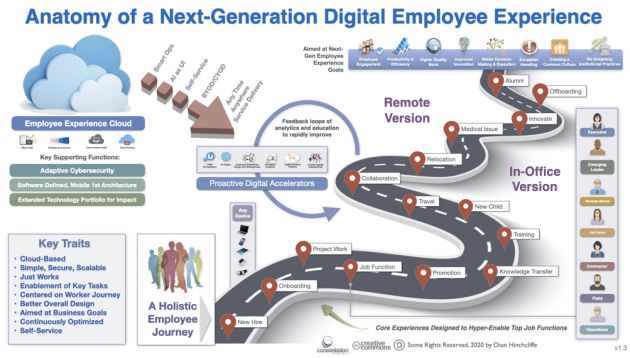

Ross: One of the most outstanding aspects of your work is your lovely visual frameworks.

Dion: Thank you.

Ross: Whatever it is you look at, you study, you come up with a diagram, which shows the relationships between ideas and the structures. How do you go about that? What’s the process? When you say, all right, I’m going to do a map of a particular domain, what’s the process you take?

Dion: I came up first in what’s called structured methodology, which is a lot about how you apply a noun and verb approach to everything. Same thing with use case notation back when the Jakobson was popular around how do we communicate processes to regular business people and get them to agree that this is what we should do and we have a common reference and understanding of things that really helped. But now, I use my diagrams as a form of sensemaking. If I can’t draw a picture of it, I don’t understand it well enough to tell you what it is.

One of the first things I almost always do is sit down with a drawing tool. I apply several different ways it could be structured/designed, or it could be an object-oriented methodology or use case based approach. But it tends to be something around noun-verb, to say, what are the things we’re talking about? What do they do? How do they relate to each other? One of the things my diagrams communicate is those things, and I’ve had people tell me, they’re way too busy, I’ve had people say until I saw those details, I didn’t understand how it worked, so it’s very interesting.

Ross: Can you dig into that noun-verb frame? Somebody who is fresh to this, how would you describe that and how they would apply that approach?

Dion: Sure. If you’re thinking about things like cloud computing, you might think about the things that you have, you have networks, and you have servers, and then what do those things do, you must have people that those things provide value to. One of the most important things and you’ll see in a lot of my diagrams that I try and put us in them. If we draw all this technology, and we’re not connected to it, we’re not in that picture, then I don’t think there’s much point. Technology for its own sake doesn’t have a lot of value.

We have to be some of those nouns in there. Who are the customers? Or who are the workers? Or what are the stakeholders? You’ll see that I tend to put both the technology pieces and us in those diagrams because without technology relating to us, I don’t think there’s a lot of value and I don’t think there should be a lot of value. It shouldn’t be for its own sake. You’ll see both the technology and the human nouns and then the verbs like the server might provide a result or an outcome over the network to that stakeholder. It says okay, now I was able to complete my unit of work or my process or write my book or post my blog or buy my product or whatever it is but you can see how we relate directly to that technology.

Ross: You mentioned a couple of other frameworks or methodologies for framing those diagrams. Are there other approaches?

Dion: I can’t remember Ross, how much you’ve been involved in software development, I think you have done some. But back in the 90s, there was the big revolution, saying, let’s not explain to computers how we work in terms of their language, what if we could explain how we work in terms of our language? So the object-oriented revolution was born. There were a bunch of people back in the day who said, let’s describe to computers our thinking in our terms. It’s more complicated than that. But that was the essence of the concept.

I had to draw many diagrams, I’ve had to go in front of boards or in front of large government institutions, and explain why they have to give us $50 million to make this diagram become a reality. You become very good at putting the business value in that diagram. To this day, I still believe that the object-oriented approach, which is also complemented later on by use-case notation, and use-case design approaches, really says let’s talk about the specific tasks, and then how it breaks down, and the concepts, and let’s explain those concepts to computers. But out of that came things like the unified modeling notation.

Ross: I was about to mention that.

Dion: Yes, I wrote a book on it. I’ve done hundreds of the things or probably even 1000s, but all of that was training. People say, what magical tool do you use to do that? Because if I have the tool, I can do what you do. I say I just use Keynote, Apple Keynote, but I can do it in any tool, I can do it in Paint, and Visio, whatever, it doesn’t matter, the hard part is being able to understand the domain. What are the other frameworks that came probably towards the end of my serious technical practice was domain-driven design by Eric Evans. That is the apotheosis that’s closest we’ve ever gotten to describing in true terms how we think, in a way that we can then easily explain to our computers and our machines in design or a framework.

Ross: Do you use presentation software, usually?

Dion: Almost always, because almost everything has to be communicated in a PowerPoint deck at the end of the day. I still to this joke that the world would be a greater place, if we had a code generator for PowerPoint, all we had to do is drive and hit the button, and out comes a system or business or whatever it is. But that’s still the primary means of conveying high-level concepts to key stakeholders. I work in the natural medium. I work directly in the tool that we’re going to use to communicate.

Ross: Do you ever use paper?

Dion: I always experiment with all the new tools. There’s a fantastic app for iOS called Paper. It’s good but it’s hard to edit in. I’ve used a lot of the design and drawing tools. At the end of the day, I’ve used the mind mapping tools, all those but you can’t get them and make them the finished product. What I find, in the way I do it is you want to be working in a finished medium whenever you can.

Ross: Right. No, I meant the old paper, before computers.

Dion: I think it’s a waste. I know you’ve had Tim O’Reilly on there and I’ve seen him write endlessly in his notebooks. I’m jealous because my worry is I can’t find that information once I record it. One of the things I do now is that I use an application called Otter.ai. It just records everything. Then it automatically extracts the structure of whatever that conversation was. I can have a 30-minute conversation with a stakeholder or a subject matter expert, then it will instantly present the summary that I can then translate into a diagram. I’ve produced thousands of my diagrams over the last 25 years. They’re all over the internet. Before I had to go through all my interviews and everything, I’ve always taken everything in digital form because it’s easiest to use, find, search, backup, and all of that. But now the tools today are just so amazing.

Ross: Yeah. When I’m doing my visual diagrams, I start usually on paper for the first 10 or 15 minutes, just because it’s a bit quicker to lay out the ideas and then I start putting it into a digital tool.

Dion: I love your diagrams, Ross. They’re fabulous and I share them regularly. The inability to edit paper is the thing that drives me quickly to digital.

Ross: Yeah, you have to move on quickly so you can move things around. It’s just for that dump and I find… what’s the relationship just quickly to lay that down? So pull back into saying, okay, we’re immersed in a universe of information. You’ve got some solid frameworks to understand what’s going on but the world is changing and there’s new information all the time. What sources do you look at? How do you scan for new signals? How do you filter those to see what’s relevant? How do you bring those into your thinking? What’s your process for making sense of information immersion?

Dion: It’s probably considered a little bit trite now, but I still use social media as my primary filter, not the filter they produce for you. Like on Twitter, for example, I create my groups, and my lists of the people who I trust and know that they’re most likely saying things that are important and worth paying attention to. I can consult them unfiltered by the main social media service, but I can access my own filter. I’ve got custom-designed lists that I go in, and look at. It’s interesting, I try to be very careful not to read too much about new things from other people until I’ve tried to understand them first because what happens is, I learned this in doing lots of design work, is that if you let your thinking be influenced too early by others, then you go down their paths, as opposed to new paths you might have discovered if you hadn’t encountered that information.

It’s very tough to be a futurist. Ross, I know you are too. You need to have some clue that something is important out there. But I might only use it as a signal. I even see them talking about it, that might be enough for me to go and try and think about it myself first before I dive into the early thought leadership that’s coming out. And that’s what I believe made me more effective. I’m trying to get the Nobel physicist who did this himself, the one who worked on The Challenger Disaster, he played the drums. Richard Feynman. That was his big thing, he would spend 10 years not looking at his peer’s research sometimes until he had his own opinion on it because he was worried that he would be too influenced. It made him extraordinarily powerful if late to the party sometimes. I tend to lean in that direction because it has worked for me very well. I think that you want to be able to see the weather, but you don’t want the local forecast until you’ve done your work on it. Otherwise, you can’t make a meaningful new contribution, which is the risk, I think.

Ross: You avoid the people who are trying to make sense of it earlier specifically?

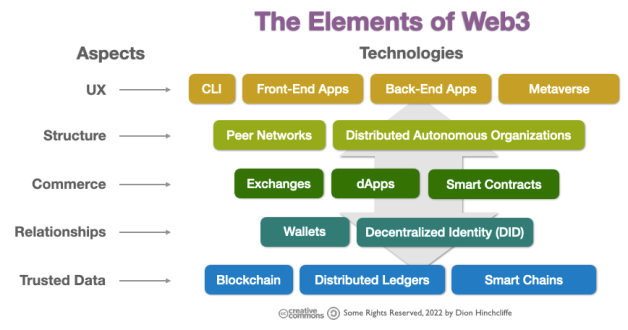

Dion: I am afraid of learning too much early on, yes. What’s nice is people have told me that I have a fresh often take on things and there’s a reason for that because I avoid reading. I always go back, at least, I try to go back and see what they said. The big topic today is web3 and it’s such an enormous topic. There’s so much being written about it, the majority of it’s not even correct or whatever. But I could tell that something momentous was happening as it did back in the web 2.0 days that you remember I was really closely involved with. But I’m five years late to that party and I’m still trying to stay out of it until I have a take that will be the one that’s going to stand the test of time. If I don’t get it, that’s okay, but I think I have a better shot because I’ve not followed too closely the details of the field.

Ross: Yeah, it is harder to pull back to form your own frame if you’ve been exposed to a lot, but in web3, there’s like 50 different angles you can come at it from.

Dion: It’s much bigger than what came before.

Ross: Everything can be fresh, as long as just a rehash of what’s already there. There are a lot more angles to bring on it. They’re not necessarily going to be more right, because it’s still this emerging field. But it is wonderful to be able to try to frame some of the potential. In a way, you start from a frame because it’s not just solely trying to explain the whole space, what is one particular frame on it, or it’s in terms of its applications or its value, that often can be the thing which brings the value is the frame that you choose to look at it from?

Dion: Yes, and you want to be able to provide something to be valuable to your peers, and to the industry in general, you need to have a take that isn’t the same, it has to be fresh, and I enjoy that. Sometimes I get to be first, it’s great. Or I get to be early enough because I thought about it. I thought about going down a road where I was able to see things farther ahead because I didn’t try and just look at the next horizon. I’d rather say where is this leading us, where does that go? I’ve also been lucky enough to call it early but I’ve also realized that it’s okay if I don’t have it, if it’s not the right thing, I’d rather wait.

Ross: So if you’re using your Twitter list, for example, and you find things, content shared there, do you then set those aside for reading? Do you bookmark them? Do you visit a place or repository where you place all of your content or ideas or thoughts?

Dion: Yes, I’ve switched over the years. Way back in the day, I use things like Delicious, if you remember that bookmarking service.

Ross: I do.

Dion: Now we’re going back in history, those were very good and they were very popular. Nowadays, I use things like Instapaper. I religiously note things and categorize them so I can find them quickly. They tend to be things I know for sure that I need to go back and read, and I often don’t go back. It could be months or years before I go back and look at them. But I know everything I’ve put there, it’s something that I judged to be significant. This is the thing that is missing a lot from teaching modern digital work skills. What is between the finding, the underlying content, and putting that into the structure?

We’re surrounded by information, but we’re never given the time or the tools to make sense of it. Sensemaking is one of the most important pieces. We’re just drowning in raw information and research and insights and thought leadership and all of this. But unless you can think about it, sit down and start to connect the pieces together, and make sense of it. It doesn’t do anything for you other than maybe you can access some facts and figures. Sense-making is a really important piece of this whole process and these tools like Instapaper, lets you gather all this and then go back and start to weave this together. It can take months or years to truly make sense of a topic or subject.

Ross: One starting point, you see something, put it in Instapaper, for example, or some other read-it-later app. On the other end, you’re creating diagrams that distill that all, where you’ve made sense of it all, and you’re communicating that. Is there anything in between that in terms of the ways in that process of sense-making, in terms of structuring or playing with ideas or letting things incubate? What do you do? What is between the finding, the underlying content, and putting that into the structure?

Dion: If you spend a lot of time or any time looking at my diagrams over the years, you’ll see that I’m never done, I tend to go back. When I understand it better, I will say, I only understood this topic to this level, and the whole world changed and the industry changed in the intervening years, so I’ve got to catch up on whether it’s cloud computing or something that’s really hot right now, artificial intelligence, or whatever it is. I’ll keep revisiting it and saying, this is not a dead subject and no one should pretend it even remotely is. I like to say, we’re in the cave painting days of virtually all of this right now.

You and I live in one of the most exciting times in human history, and we’re at the very beginning of probably the biggest transformation that humans have undergone. That’s what I believe. I go back and look at this information when I believe I’ve come to an arrival point in my thinking that I go back and say, all right, what did they say? And often they do have things that I didn’t consider. But I’m gratified that I often have things that they didn’t consider. Then I might merge those. I’ll take the best. We build on the shoulders of giants. There’s no shame about and I try and give credit where it’s due. If someone really did some notable thinking, when I go back and look, I missed that, then I will try and credit them. But then I build a new visual. This might go on for a decade or more sometimes.

It’s amazing. I was one of the very first analysts to cover Cloud in a big way, still covering it, doing keynotes all over the place on the topic. Still, we’re at the very beginning of the story, which most people don’t realize. I’ve put like now these visuals are 10 years out, here’s what’s likely to happen. Even though it is crude compared to what’s going to happen so it’s exciting. But yeah, I go back and it’s like an agile process over a long period where I go back and revisit, I see what people said after I arrive at conclusions, then I update everything and try to give credit where it’s due as much as we can, and then revisit everything, my visuals, my research reports, and things like that.

Ross: Same for me. Anything which I’ve done before is just a reference point for filtering and then refining. I always in my diagrams put beta at the top, just to be able to say this was the first version. It’s always frustrating because I put it out as beta saying, hey, have you got any feedback? Everyone’s like, Oh, that looks good. They never give me any feedback because it’s sort of that feeling it was finished, but I never thought it was finished. It was always just a starting point.

Dion: Exactly. I don’t do that. People mostly know that but I do say not exhaustive because the story is never going to end. Some of these do conclude it is interesting, but most of them have just gone.

Ross: We’ve mentioned it before, are there any new tools, or software tools that you think are interesting or worth looking at, or you’re playing with?

Dion: Yes. I’m utterly fascinated by the potential of generative AI. We’re now getting these amazing frameworks, where you just describe what you want, in a declarative way, you say here’s what I want and it does most of the really heavy lifting in visualizing things. I’m looking at this one new AI application. I can’t remember what it’s called. But you just give it a very high-level script, and it creates this incredibly dense, high-quality video of what you’ve just described to it. I’ll have to look it up for you to post in the comments later. But these are the types of things, it’s next level. Otter, that narration software can read the entire conversation and create an outline and summarised bullet points on what you talked about. We now can, it’s interesting, do the reverse process as well. You’ve probably seen the WOMBO art app?

Ross: No, I haven’t.

Dion: It’s downloaded out of the App Store. It’s truly amazing. It’s WOMBO.ai. You give it a few words or as many words as you want, and it will drop a painting that contains everything you described, and it’s quite artistic. You can even choose a style. I was like, that’s impressive but that’s not useful for business purposes. But these new generative AIs are able to take our high-level conceptual descriptions and create incredibly compelling visual video content depicting these ideas. It’s really narrative and very human-centric. I’m just now starting to play around with these but AI is now becoming this tool that everyone can use to create communicative resources that can help everyone and do it in a fraction of the time. Also, people who don’t have 25 years of experience doing it, like me doing it, can do it in just a few days. It’s very interesting.

Ross: One of the most important insights from AlphaGo beating all of the best human players at Go was the fact that the best Go players in the world, a game which has been played for two and a half millennia, learned strategies that they had never come up with before. We are learning from the AI how to do better as humans at a very conceptual, a very intellectual frame, not just in terms of tactics or strategies or anything tactical, but just these whole new strategies or frames of thinking.

Dion: I actually did follow that a little bit. I do always say, look, we actually didn’t build that but it’s not like we don’t get some credit for that. I think that’s important. I always really try and bring that human aspect back, we are co-evolving with our art and creations. This is not happening in a vacuum, and that’s very encouraging. We also must be extremely careful not to take maybe the downsides of humans and encode them into AI. Unsupervised machine learning is very interesting because it does discover things that we never anticipated. That’s the whole point, is to say, what questions aren’t we asking? What are ways of thinking that we have not even thought of should we be considering? Yes, it’s a very interesting time.

Ross: Are there things which you think you could do to develop or work on in terms of enhancing your information and insight and communication methodologies?

Dion: It’s interesting, I’m torn about it but video is now the new way to communicate. You or I tend to prefer the text description, we grew up in a way where we learned to read everything very, very quickly and process it. I now have seven-year-old twins. I know that they’re growing in a much more visually rich universe than we ever even could conceive of. You and I probably grew up in just a handful of channels on fixed programming. They have unlimited channels that are always trying to give them what they most want to learn next, or most want to know or experience next. These things have AIs that study what they learn and try to give them more of what they want. That’s both good and bad.

My son is amazing. He watches science videos all day and all it is is trying to figure out what other science things he wants to know and give it to him. It’s amazing. My daughter is less so. But it’s incredible. I’m moving more towards streaming content, I’m trying to create the video version of my visuals, which is why I’m experimenting with it. I have these different AI frameworks right now, that can take my ideas literally as I described them. If I can describe them in use case format, it can build the video to explain them in a really compelling, human-centric way.

My latest content has much more video, but they’re mostly handbuilt. They’re okay, but they’re nothing good compared to what I’ll be able to do in a year or two. I’m going to move into the video world and then hopefully break into Tiktok or who knows what’s going to be hot in the next couple of years. But video content is the future. If we can create content that can be consumed as quickly as text, that would be a breakthrough. I’d love to contribute to that. I don’t know if I’ll get that far. The highest resolution, the highest bandwidth connection we have into the human brain is to the eyes. That’s one of the reasons I do visuals.

I’ve had more people tell me I never understood something until I saw your visual. I didn’t understand that. We’re on the cusp of being able to create video content that can tap more directly into the human brain. I would love to be able to have even a minor breakthrough in that. I think with the tools we have, you and I could probably get there. We’ll need to get there to get to the next level of human accomplishment. That’s my stretch goal. We’ll see how far I get.

Ross: That’s fantastic. You’re inspiring me to try to do some similar stuff. That’s fantastic. Let’s coordinate on that. I’d love to see anything, which you do.

Dion: I’ll send you what I’m working on.

Ross: Yeah, any concept or frameworks, and try to make them visual and compact. Do you have any recommendations for our listeners? What would you suggest to them to help them thrive on overload?

Dion: If you can’t explain something in a sentence then you don’t understand it, so it always goes to that state. If you’ve got thirty seconds to explain even the most complicated concept, and you can’t do it, if you can’t explain something to the three-year-old, you don’t understand it. Try and get there first, then break it down into its constituent components. What’s the simplest set of things that could describe that and then see if you can draw a picture around it. That’s all you have to do. It’s simple as that, and that heuristic will get you far. If you’re able to do that, you’ll be able to communicate your ideas and convince other people.

Ross: That’s fantastic, thank you so much for your time and amazing insights. It’s lovely to speak with you. Thank you for sharing.

Dion: Thank you so much, Ross. I appreciate being here.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download