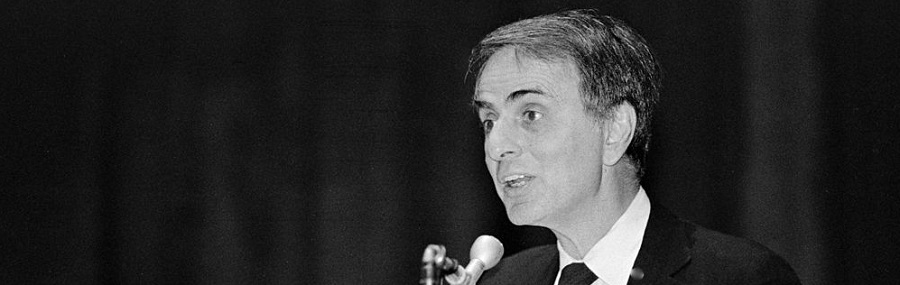

Carl Sagan was one of the all-time great science communicators. His TV series Cosmos has been watched by over half a billion people, but more importantly through his life he helped millions of people think and assess information from a more scientific frame, encouraging skeptical inquiry.

The fine art of baloney detection

Sagan’s outstanding essay The fine art of baloney detection best distils his perspectives and insights on the subject into a set of tools any of us can apply and use in our everyday lives.

Everyone should read the whole essay, but the essence is distilled in what he describes as a ‘baloney detection kit’.

In the course of their training, scientists are equipped with a baloney detection kit…

What’s in the kit? Tools for skeptical thinking.

What skeptical thinking boils down to is the means to construct, and to understand, a reasoned argument and—especially important—to recognize a fallacious or fraudulent argument. The question is not whether we like the conclusion that emerges out of a train of reasoning, but whether the conclusion follows from the premise or starting point and whether that premise is true.

Among the tools:

· Wherever possible there must be independent confirmation of the “facts.”

· Encourage substantive debate on the evidence by knowledgeable proponents of all points of view.

· Arguments from authority carry little weight—“authorities” have made mistakes in the past. They will do so again in the future. Perhaps a better way to say it is that in science there are no authorities; at most, there are experts.

· Spin more than one hypothesis. If there’s something to be explained, think of all the different ways in

which it could be explained. Then think of tests by which you might systematically disprove each of the

alternatives. What survives, the hypothesis that resists disproof in this Darwinian selection among

“multiple working hypotheses,” has a much better chance of being the right answer than if you had simply run with the first idea that caught your fancy.

· Try not to get overly attached to a hypothesis just because it’s yours. It’s only a way station in the pursuit of knowledge. Ask yourself why you like the idea. Compare it fairly with the alternatives. See if you can find reasons for rejecting it. If you don’t, others will.

· Quantify. If whatever it is you’re explaining has some measure, some numerical quantity attached to it, you’ll be much better able to discriminate among competing hypotheses. What is vague and qualitative is open to many explanations. Of course there are truths to be sought in the many qualitative issues we are obliged to confront, but finding them is more challenging.

· If there’s a chain of argument, every link in the chain must work (including the premise)—not just most of them.

· Occam’s Razor. This convenient rule-of-thumb urges us when faced with two hypotheses that explain the data equally well to choose the simpler.

· Always ask whether the hypothesis can be, at least in principle, falsified. Propositions that are untestable, unfalsifiable, are not worth much. Consider the grand idea that our Universe and everything in it is just an elementary particle—an electron, say—in a much bigger Cosmos. But if we can never acquire information from outside our Universe, is not the idea incapable of disproof? You must be able to check assertions out. Inveterate skeptics must be given the chance to follow your reasoning, to duplicate your experiments and see if they get the same result.

Sagan’s toolkit is even more valuable and relevant today than when he first shared it. Let’s learn to apply it and help others to discover its value.

Image: Wikimedia