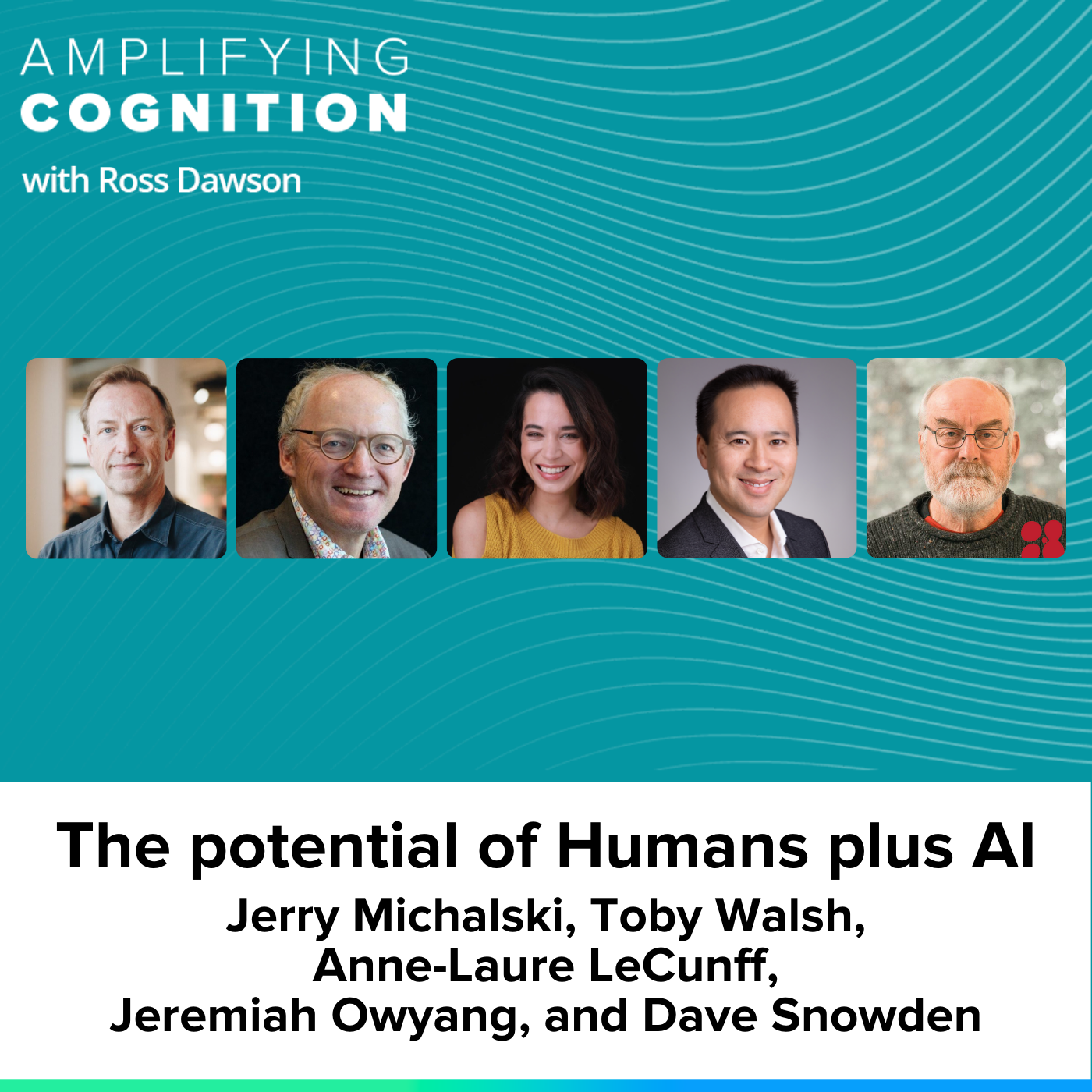

About this episode

We return with another compilation episode, this time looking at the potential of Humans plus AI. You will hear insights in brief excerpts from the current season of the podcast from Jerry Michalski – Episode 2, Toby Walsh – Episode 14, Anne-Laure LeCunff – Episode 5, Jeremiah Owyang – Episode 9, and Dave Snowden – Episode 24. To tap the potential of AI we need to take a deeply human approach. These leading thinkers share how we should be thinking about the relationship between humans and AI and how we can put that into practice.

What you will learn

- Becoming better cyborgs, navigating AI, creativity, collaboration, and ethics

- Navigating the controversy of AI-generated patents and the synergistic relationship between human inventors and AI assistants

- Unleashing AI as a thinking partner for enhanced creative endeavors

- Amplifying humanity, navigating the collaboration of humans and AI

- Navigating the intersection of human cognition and AI, dangers, opportunities, and abductive reasoning

Full Episodes

Transcript

Jerry Michalski

Ross: How, Jerry, could we become better cyborgs?

Jerry: Part of it is understanding how the tools work and what the limitations are, and not becoming the lawyer who submitted a brief that they fact-checked using the tool that generated the hallucinations and therefore got themselves really embarrassed in public a month or two ago. You don’t want to be that guy. There are a lot of ways to avoid those errors. Understanding how the tools work and what their limitations are, lets you then use them well to generate creative first drafts of things.

One of the enemies of mankind is the blank sheet of paper. So many people are given an assignment, and they’re like sitting down, and it’s just like, No, and you ball up two words, and you throw it in the trash. And here, all of a sudden, you can have six variants of something put in front of you. We need to become better editors of generated texts. Then the other piece of being a better cyborg is not about being a lonely cyborg. But what does it mean to be in a collective of cyborgs? What does it mean to be in a cyborg space? What does it mean to co-inhabit cyborg intelligence with other people and other intelligences that are just going to get faster and better at this thing? I think it’s really urgent that we figure out the collaboration side of this so we don’t think of it only as, Well, they gave everybody a better spreadsheet and now everybody’s making a lot of spreadsheets, this is different; this is different in type.

The third thing I would bring in is the ethics of it, which is boy, it’s easy to misuse these tools in so many ways. Unless we understand A – how they work and what they’re doing, but B – have some better notion ourselves of what is right and what is wrong to do, and some relatively strong idea of what is right and what is wrong to do, then this is going to evolve. There’s one school of thought. Bill Joyce said this years ago: There is no more privacy; forget about it; privacy is overrated. And the other realm is like what the EU is doing right now, with new privacy regulations. They’re really working hard to try to figure out how to protect us from having our data just sucked out of our lives and used by other people to manipulate us in our lives, which is what capitalism wants to do.

It’s not as easy as I’m going to get good at Photoshop, Final Cut, or whatever, and become an ace with some software. I point to those kinds of people as the early cyborgs. I’m like if there’s any piece of software where you no longer think of the commands, maybe you’re a spreadsheet ace and you do these massive, incredible models with pivot tables and who knows what, and the software you’ve internalized so well that it doesn’t even come to consciousness, you’re down this road of cyborgness. But this is more complicated than that because the issues are so important and because we can now collaborate and communicate better all of those issues.

Toby Walsh

Ross: One of the very interesting examples you used was an AI patent generator called DABUS. The person who created it said that it essentially was an AI inventor and tried to patent it in the name of the AI. You pointed out that, in fact, of course, the person invented the system and it was really just an assistant to him. There was a human plus AI endeavor, as opposed to something that you could attribute fully to the AI.

Toby: Indeed, yes. It’s a very interesting example. There was a court case brought in the US and one in Australia where briefly before the initial judgment was overruled, the AI was actually allowed to be named on the patent as the inventor, but that now has been overturned, at least in the US and Australia. Again, we returned to the place where only humans are allowed to be named as inventors. But the system, as he says, is an interesting example of how humans can be helped. These are really powerful tools for helping people do things that we initially thought required quite a bit of intelligence, coming up with, there’s nothing perhaps more endemic of what is something that’s intelligent is to come up with something that’s patentable. There is a certain mark there that it must be novel, and done something truly creative, otherwise, you wouldn’t be allowed the patent.

DABUS helped Steven Tyler, the guy who wrote the program, to come up with a couple of ideas that have patents that have been filed for. A fractal light. The idea is that you turn this light on, and it flashes in a fractal way. Fractal is that it doesn’t have any repetition in it. The frequencies keep on changing. That will attract our attention, obviously, because it is not going to be flashing like a lighthouse, or in any rhythmic way. It’s actually going to be disturbing our mental perception of it. It will actually be quite a good way of attracting people’s attention. Then another example is, interestingly, we have both fractal inventions, a fractal container. The idea is that the surface of this container would have a fractal dimension to it. Again, if you know something about fractals, it means it’s good to have a huge, truly fractal, in fact, infinite surface area. If you want to have something where you can heat up the container very easily, then having a large surface area to the volume will be very useful.

What’s interesting is that these are the only AI programs that are being used by people to help invent stuff. What people do is that they get the program to define what you might call a design space, a set of ideas, and building blocks that you put together. Of course, the great stake of a computer will be very exhaustive and do things in all the possible ways. Maybe our human intuitions will stop us from doing some of the more extreme, unusual ways, putting these things together. But the computer will beautifully peer it as it won’t be inhibited in those ways. It puts all these things together in interesting ways. But the problem is that it is huge, actually infinite design space. You’ve got to tame it in some way. You’ve got to say, what are the interesting ways of putting things together, and then we come to this ill-defined word interesting.

This is where there was a synergy between the human and the AI, which was that it actually outsourced the idea of saying, what’s an interesting promising direction to follow. If I’m trying to build up this idea, it’s going to be a fractal container or a fractal light. He pushed it in those two directions. Then it’s like, okay, let us explore a bit more about in what way is the light fractal. He kept on deciding which of the many possible combinations of concepts that he was trying to put together to go off and follow because it was a hugely branching, in fact, infinite search base to explore. It was playing to the strengths of the computer is exhausting this ability to put things together irrespective of how silly they might sound. Then the human who was bringing the judgment and the taste of what might be interesting, what might be a promising direction to follow.

Anne-Laure LeCunff

Ross: That’s awesome. You’ve been looking at AI and its potential for creativity. One of the phrases you use around AI is to enhance our creativity or to emulate our creativity. I’m more interested in the enhancement. I’d love to hear about any approaches that you use or the way you think we can use AI to enhance our creativity.

Anne: I’m just going to share my favorite prompt because I could talk about this at length. But I’m just going to share my favorite prompt that I use all the time. What I’ll do is I will write something that I’m working on, it could be a paragraph that could be for my book, that could be for my blog, that could be a script for a youtube video, could even be for a research paper for my Ph.D., I will do my best to write the best version possible of what I think covers everything. Then I will copy and paste it into ChatGPT and I will ask, what am I missing? That’s it. That’s the prompt. What am I missing? Every single time, there will be at least one thing, one blind spot, something that I forgot to address.

Some of the things that ChatGPT will come up with, I’ll be like, well, that’s not really relevant so I’ll just ignore it. But there will always be one thing where I’m like, huh, oh, wow, that’s really interesting. So I’ll go and I’ll research this and I will augment the final piece with that aspect that I completely didn’t see in the first place. In that sense, I can use AI as a thinking partner. I can get to the same result very quickly that I would get, and I still get, and that’s not replacing it because I enjoy doing this, but having a long conversation with a friend, where you’re telling them, hey, I’ve been thinking about all of these things and then you spend a whole evening together discussing those ideas.

I often actually take notes after spending an evening with a friend chatting about different things, because by the end of the evening, there will be several questions the friend asked, several topics that you ended up exploring that you didn’t even imagine were connected with what you were discussing in the first place. This is a shortcut to that. It’s a thinking partner. It’s a lot faster. I do feel that my work is a lot better in the end than if I just relied on just me thinking about everything and every angle.

Ross: Yes, I think that’s one of the best uses for it. Similarly, I also say, okay, this is what I’ve thought, what else is there? Or similar. I think GPT for red teaming, as in challenging, you bring and say, well, what’s wrong with my argument? Or how could it be improved? Or what’s missing? Or all of these other things, I think are one of the strongest ways to do it. Two broad approaches. One is you say, Okay, let’s start GPT to do something and you can work on it if you’re having writer’s block, whatever, but the other is you come up with everything, and then you throw it in and you see what can be added to it.

Anne: Yes. In both cases, I think it’s paying off your strength and its strength. I think, at this stage, at least, it’s not a really good writer. I haven’t seen any AI right now that can write like a human being does. It can write a basic, SEO-level type of article, but if you want to write something that really moves people, that makes them feel connected, at this stage, we’re not there. It’s interesting, I don’t know if we’ll get there, because the way it’s trained is on everything. So you get to this average level of writing that is not necessarily the best that can be produced by a single human being that really pours their heart into something. But as a sparing partner, a thinking partner, red teaming, as you said, I think it’s excellent, absolutely excellent. This is for me, one of the top ways it should be used.

Jeremiah Owyang

Ross: We’re particularly interested in Humans plus AI. Humans are wonderful, AI has extraordinary capabilities. For the big picture frame, how should we be thinking about Humans plus AI, and how humans can amplify their capabilities with AI?

Jeremiah: I think that the verb “Amplify” is correct. There is a book written by Reed Hoffman, co-written with a friend of mine called Impromptu that talks about AI amplifying humanity. That is the right lens for this. All tools that we’ve built technologies throughout the course of human history have done that, from fire to splitting the atom to technology to AI. I do believe AI is at that level, it is quite significantly going to change society in many ways. The goodness of what humans desire, this tool will do that; the bad players, these tools will also amplify that.

It’s for us to determine the course of how these technologies will be used. But there’s something different here, where the experts I know believe that we will see AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) equal to human intelligence within the decade. This is the first time, Ross, that we’ve actually created a new species in a way. I think that’s something quite amazing and shocking. These are tools that will amplify what we desire as humans, what we already do.

Ross: If we think Frame AI as a new species, as you put it, as a new novel type of intelligence, one of the key points is that it’s not replicating human intelligence. Some AI has been trying to model human intelligence, and neural structures, and others have been taking other pathways. It becomes a different type of intelligence. I suppose if we are looking at how we can complement or collaborate, then a lot of is around that interface between different types of intelligence. How can we best engineer that interface or collaboration between human intelligence and artificial intelligence?

Jeremiah: That’s a great question. I think that we can use artificial intelligence to do the chores and the repetitive tasks that we no longer desire to do. Let’s acknowledge that there’s a lot of fear that AI will replace humans. But when we dig deeper into what people are fearful of, they’re more fearful of the income loss that they’ll have in some of the repetitive roles. It’s not always the things that they have sought after to do in their career. It’s just the way that they’ve landed in their career and they’re doing tasks that are repeated over and over. But if it’s just using your keyboard and repeating the same messages over and over, that is really not endearing to the human spirit. This is where AI can help complement so we can level up and do tasks that require more empathy or connection with humans or unlock new creative outlets.

Ross: One thing is a division of labor. All right, Human does that, AI does that or robots do this.

What is more interesting is when we are collaborating on tasks. This could be from anything like, ‘I’m trying to build a new product.’ There are many elements within that where Humans and AI can collaborate. Another could be strategic thinking. In terms of how we build these together, rather than dividing, separating, and conquering, where is it that we can bring together to collaborate effectively on particularly higher-level thinking?

Jeremiah: Yes, those are great things. AI is great at finding patterns and unstructured data, which humans struggle with doing. Humans are often able to unlock new forms of thinking in creative ways that are not currently capable of being done by machine learning or Gen-AI. Those are the opportunities where we segment the division of labor. I want to reference, I had the opportunity to interview Garry Kasparov, Grandmaster Champion of chess, at IBM of all places, and his thinking is that we want to look for the Centaur. He believes the best chess player in the world will be a human, and she would also be using the AI. He wants to create a league where the humans with AI would be combating another human with AI in a chess battle. He believes that would be the greatest chess player ever. It’s not just a human or not just an AI, but it’s that centaur, that’s a mixture of the species coming together. And I think Garry is right.

Dave Snowden

This takes us back to the beginning in the sense of abductive reasoning being a human attribute and AI using very different structures. There are dangers in using AI to support our cognition, decisions, framing, thinking, and experience, but there are also, we would hope, some opportunities. I’d love to frame the current divide between what we frame as AI in terms of its thinking structures and human cognition, and where those could be brought together to create something better than the sum of the parts.

Dave: I wouldn’t be worried if it was going to be intelligent. But it isn’t. It’s just a super-fast set of algorithms. That’s what’s really scary about it. There’s a book by Neal Stephenson (he and I have worked together with the Singapore government) called ‘Dodge in Hell‘, which generally is a bad book apart from the first three chapters which are brilliant which basically positive future in which only the rich can have their information curated. Everybody else is sold to an algorithm. There’s an example of somebody crucifying themselves because they sell to a religious group who want as an example. To be quite frank, that’s pretty close to where we are, there are AI bots now that tailor a lie to people and give it to them on social media as they’re approaching the ballot box.

This stuff is significantly scary. The recent debacle really worries us because the people who wanted to inhibit or at least know how to control these things lost out to the religious AI people, who are within the American tradition of the rapture, they think miraculously AI is going to save humanity. That really worries me. Also, they can’t think abductively, and by the way, I’m dyslexic. Dyslexics think abductively all the time, and we can’t understand why other people haven’t seen the connections. I can’t read a book aligned to time other than with significant effort because I’m looking for patterns. What we can do, and this is where we did our original work on DARPA, is the big thing on AI is what are the training data sets?

We originally developed the software SenseMaker to create epistemically balanced training datasets to avoid the problems you see in stochastic parrots, which was written by a Google employee and published by an ex-Google employee because Google didn’t like what she and the co-authors said. Rag isn’t enough. the real focus needs to be on training datasets. Now, if you do that, and this is our stage three estuary, which we’re going to become into next year, the year afterward. Then I can create what is called anticipatory triggers. I can use past terrorist examples. I can use examples of people finding novel solutions to poverty, etc. to trigger humans very quickly to pay attention to something which is sowing a similar emergent pattern.

We are not saying there are two things that start to replace scenario planning because scenario planning relies on some historical data in some way or other, it’s not just imagination. Two ways in which we can handle that; one is estuary mapping is a new foresight tool. Because whatever has the lowest energy gradient is what’s likely to happen next, and that’s probably more predictable than the scenario. The other is to create training datasets from history at a micro level. This is the decomposition that can trigger alerts so that human beings will pay attention to anomalies before they can become very anomalous.

That’s a key principle in complexity. It’s called weak signal detection. You want to see things very early so you can amplify the good things and dampen the bad things. Conventional scanning only comes to them late. With the right training datasets and the right algorithms, we can hugely improve that capability in humans. There are things we can do with it. But the main danger at the moment, to be honest, is that human beings will become dependent on it, and human beings like magical reasoning. I can smell snow coming in, but my children can’t. It doesn’t take long for humans to lose capability.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download